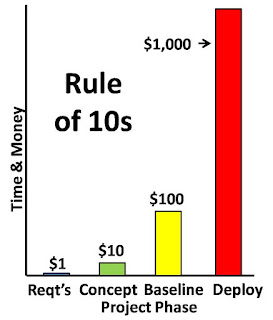

The fundamnetal characteristics of all business financial transactions are the amount of the transaction and the date of the transaction. These two components are equally important in financial planning and tracking systems. Traditional financial planning and tracking systems are not compatible with the project environment.

Traditional financial planning and tracking tools do not fit the project context. For instance, the traditional financial planning tools are tied to annual budgeting cycles not project schedules. Also, traditional financial planning tools assume the business will be in the mode of continuous operation so if activity slows in one area, the resources will be shifted to another and the expenditures will stay constant. This levels out the resource requirements and eliminates spikes and valleys in resource needs. However, projects often don't operate in that fashion. Projects activities are planned with start and stop dates and resources are assigned and removed from the project plan throughout the project life-cycle. Therefore some of the major assumptions on which financial planning tools are based are invalid in the project planning environment.

Further, traditional financial accounting systems make some assumptions when tracking costs that are not valid in the project control environment. For instance, the tracking cycle used in financial systems is based upon calendar events such as end of month, end of quarter, or end of year because these are major reporting points to taxing authorities and investors. However, the significant project reporting points are the project milestones; which seldom precisely align with finanical calendar dates. An additional assumption in the financial systems is that the business is on-schedule - again because of the financial planning calendar it is impossible for the business to get behind schedule. There is no such thing as stretching December out to have 37 or 38 days. The financial control system assumes the project is always on schedule, so any over-spending or under-spending during a time period is a true over-run or under-run on the project. However, a project is seldom precisely on schedule, and over-spending in one month may be the result of activities being delayed or accelerated and do not necessarily indicate the final project spending will be over-run.

The Earned Value Analysis (EVA) technique takes into consideration the project context for the planned and actual expenditures and integrates the project scope, schedule, and resource characteristics into a comprehensive set of measurements. This page will outline the use of Earned Value Analysis by addressing Financial Databases for EVA, Earned Value Definitions, Establishing Earned Value Budgets, Determining Earned Value, Variance Analysis, and Forecasting.

The Earned Value technique allows for the temporary and intermittent nature of project work by scheduling the expenditures based upon the project plan, including the spikes and valleys in resources requirements. Further, Earned Value tracks how much money has been spent on the project in relation to how much project work has been accomplished. This takes into consideration all that has happened on the project such as schedule delays or acceleration. The variances that have occurred can then be separated into those due to timing, either ahead or behind schedule; and those due to mis-estimating the work; true under-runs or over-runs. Finally, the indices and variances generated by the Earned Value technique will aid the project management team in forecasting the financial conditions at project completion.

Financial Databases for EVA

The EVA techniques manipulate information gleaned from three essentially independent sources of financial data. Each of these are a cost baseline for the project. Each looks at the project from a different perspective.

The planned project expenditures (Planned Value) from project start until the present time. This is established at the time the project was initially planned and represents the original intent of the project team. It is developed by summing up all of the project task estimates and time-phasing them based upon the project schedule.

The actual project expenditures (Actual Cost) as of the present time. This is collected by the business financial cost accounting systems. These are all the costs associated with the work that has been completed on the project up through the present instant in time.

The actual project progress (Earned Value) which is the originally planned expenditures for the work that has been accomplished up to this time. This is determined by the tasks that are completed or the progress made on the tasks that are underway. The key to this measurement is that the values for each task are based upon the originally estimated values for the task. Each task is assigned a "value" that is embodied in the original task estimate. When the task is completed, the estimated value represents the value earned by completing the work on the project task - regardless of how much that work actually cost.

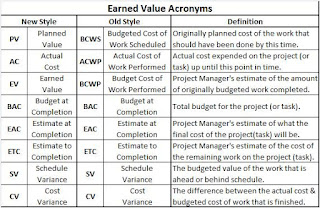

Earned Value Definitions

EVA is known for its acronyms. This table shows the acronym, using both the old naming convention and the new naming convention. Each of the acronyms is defined in more detail below.

Planned Value (PV) is developed by first determining all of the work, or tasks, that must be accomplished for a successful project result. The work within each of the tasks, whether done internally or outsourced, is estimated. That estimate is converted into a monetary value which represents the dollar portion of "planned value" of the task, essentially saying that the task has that worth to the business. This value is then scheduled to occur based upon when the task is scheduled to occur within the project plan. Once the amount and timing is established, the PV for the task or activity is set. It can only be changed by implementing a project change.

Actual Cost (AC) is the number that finance often is most concerned about because this represents the actual cash that the business has had to expend on the project. The AC is determined based upon the accounting system's method for cost accumulation. Where possible, it is most helpful to collect the costs based upon a project charge number or account number that is associated with the costs. This number may change every day based upon whether project work was conducted upon that day.

The Earned Value (EV) comes from an assessment by the project management team as to the amount of progress they have made on each task in the project. Often this is difficult to measure precisely and is based upon a judgment call by appropriate individuals within the project. Tasks that are completed have earned the entire value for that task. Tasks that have not been started have not earned any value for that task. Tasks that are partially complete may have earned some value for the work that has been done. The total amount of value available for a task to earn is the value assigned to that task at the time of project planning--in other words, the Planned Value for that task. It is easy to determine EV for tasks that have been completed (EV is the task PV) and for tasks that have not started (EV is zero). The difficulty comes when estimating the EV for a task that is underway. Suffice it to say, most organizations have set some specific ground rules in this area to ensure the EV is not under-stated or over-stated. Methods for determining EV are discussed below.

The remaining acronyms will be explained in more detail as variances and forecasting are discussed later on this page.

Establishing Earned Value Budgets

EVA is based upon task or activity planning data and therefore requires that a relatively rigorous planning approach is used, often using the bottom-up estimating rather than top-down. The project PV at any point in time is determined by summing the task-level budgets for the time period in question. Accuracy in the task level budgets is required both in the amount of effort estimated for the task but also in the timing of when those efforts will be expended. The key here is that we want to estimate the project task timing in the same way that the financial system will record the AC for the task. In most businesses, the personnel costs are collected and analyzed either weekly or biweekly because of the need to run payroll. Therefore I recommend that the in-house labor in a task should be spread evenly during the task duration, which is called "level-loading," while tasks that have external expenses often are recorded in a lump sum based upon when the supplier submits an invoice. For instance, an invoice received from a testing service would come in as a charge on one day although the testing may have occurred over a period of several months. In those cases it is often better to "event-load" based upon the expected timing of the receipt of the invoice. It is even possible to use a combination of timing approaches when estimating the PV for a task.

Selecting the appropriate timing is important so as not to create confusion later when we determine variances. A variance due to planning the timing of a task expense differently than the time when the expenses actually occurs, even though the amount is accurate, still generates the need for a variance report. Creating a task-level budget that accurately reflects the timing of expenses will reduce the need for a variance report for timing reasons. Variance reports will focus on true under-runs or over-runs.

Determining the Earned Value

Determining the EV for a partially completed task is at the heart of EVA. Therefore it is important that the EV be as accurate as possible. However, EV is a judgment call while a task is underway. If the project management team under-states or over-states the EV, they can change whether a project is perceived to be running well or in significant trouble. Over time some approaches have been developed for estimating EV. These provide guidance to the project management team and can improve the accuracy of the EV.

The best approach is to have detailed tasks planning with a percentage of PV assigned to each item or interim milestone within the task. Then as soon as that item is complete, that amount of EV has been earned. However, this does require very detailed task planning and often that planning has not been done, either to save time or because there are no obvious interim steps within the task.

Another technique is the "0-100" technique. In this approach, no EV credit is allowed for a task until the task is completed. This is a good approach for short, discrete tasks, such as "Place Purchase Order."

The "50-50" technique is also commonly used. In this approach half of the EV is credited to a task once the task is started and the other half is credited once the task is complete. This is usually done when the task is relatively long and will span multiple reporting periods. This emphasizes the start of tasks and encourages tasks leaders to begin work as soon as possible on a task.

My personal favorite of the quick estimates is the "30-70" technique. In this approach 30% of the EV is credited to a task at the time of the task start and the remaining 70% is credited when the task ends. This is a good approach to use when a task has an uncertain estimate, such as software debugging. There is the recognition that work is underway, but the emphasis is on completing the task.

Earned Value Variance Analysis

EVA provides excellent insight into project variances. Through EVA a project manager can understand how schedule variances are impacting cost variances and vice versa. Without EVA, the project manager is at a disadvantage when trying to explain to finance why the expenditures were other than expected.

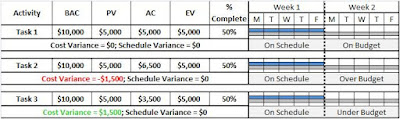

Once we have the PV, AC, and EV for a project, we can begin to calculate project variances and determine the current status of the project. The first variance I will discuss is Cost Variance (CV). This is the amount of under-run or over-run the project has experienced. As with all of the measurements, I can address the Current CV, which is the variance this month, or the Cumulative CV which is the variance since the project started.

CV = EV - AC

In EVA, a negative CV is an over-run and a positive CV is an under-run.

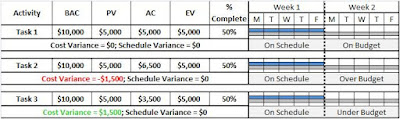

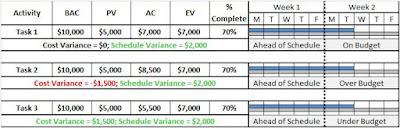

With the Earned Value technique, the CV is calculated by subtracting the AC from the EV. This is essentially asking, "How close am I to what I thought it would cost do the work I have accomplished as compared to what it actually cost to do the work that is accomplished." Because both EV and AC are only considering the work that is actually accomplished, the errors due to schedule variance are removed. The first set of figures shows how a project that is on schedule, but is either in an under-run or over-run condition, would be reflected in both a Gantt chart and with EVA data. The task is a two week task that started one week ago. The task is on schedule, meaning it is 50% complete and therefore the EV is the PV. In the top case, the task is on budget so AC = EV and the CV is zero. In the second case, the AC is $6,500 but the EV is only $5,000 so the CV is -$1,500 and the project is over-run. The third case shows that the AC is $3,500 and the EV is $5,000 so the CV is +$1,500 under-run.

Next we will consider Schedule Variance (SV). This is the amount ahead of schedule or behind schedule the project is currently experiencing. An interesting point about SV is that it is measuring schedule but the units are dollars. SV measures the VALUE of the work that is ahead or behind schedule, not the number of days or weeks. As with all of our measurements, we can address the Current SV, which is the variance this month, or the Cumulative SV which is the variance since project start.

SV = EV - PV

In the Earned Value technique, a negative SV is a behind-schedule condition and a positive SV is an ahead-of-schedule condition.

When considering the value of work that is ahead or behind schedule, the value of any under-runs or over-runs needs to be excluded. The Earned Value technique compensates for this. With the Earned Value technique, the SV is calculated by subtracting the PV from the EV. This is essentially saying, "The value of the work that I have completed minus the value of the work that I had planned to have completed by this time." Because both EV and PV are only considering the work using the originally estimated value of the work, the errors due to cost variance are removed and variances are due only to timing.

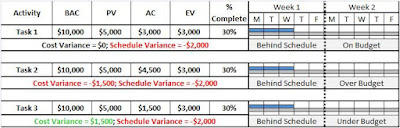

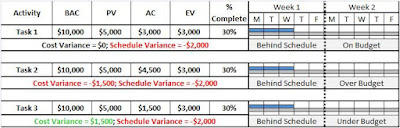

The next set of figures shows how a project that is behind schedule, and is either in an under-run or over-run condition, would be reflected in both a Gantt chart and with EVA data. The task is a two week task that started one week ago. The task is behind schedule, it should be 50% complete but it is only 30% complete and therefore SV is -$2,000 in all three cases shown. In the top case, the task is on budget since the AC of $3,000 matches the EV for the work that is done. In the second case, the AC is $4,500 but the EV is only $3,000 so the CV is -$1,500 and the project is over-run. Notice, that the project is not over spent at this point. Without the EVA analysis, the project team could be fooled into thinking they are in an under-run condition. In actuality they are over-run and behind schedule. The third case shows that the AC is just $1,500 and the EV is $3,000 so the CV is +$1,500.

A project may have spent the exact amount of money up to a point in time that had been budgeted for that time period. However, if only half of the work had been accomplished, the EV would be one half of the PV. This would indicate a significant behind schedule condition and a significant over-run, even though the money that had been spent was exactly what had been in the plan for spending up to that point. The problem is that now there is no money budgeted to do the work that was scheduled to have been done but has not been completed.

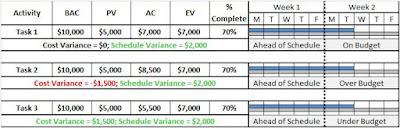

The final set of figures shows how a project that is ahead of schedule, and is either in an under-run or over-run condition, would be reflected in both a Gantt chart and with EVA data. The task is a two week task that started one week ago. The task is ahead of schedule, it should be 50% complete but it is already 70% complete and therefore SV is +$2,000 in all three cases shown. In the top case, the task is on budget since the AC of $7,000 matches the EV for the work that is done. In the second case, the AC is $8,500 but the EV is only $7,000 so the CV is -$1,500 and the project is over-run. The third case shows that the AC is just $5,500 and the EV is $7,000 so the CV is +$1,500. In this case, without the EVA analysis the project team could be fooled into thinking they are over-run since they had spent more than the $5,000 that was budgeted to be spent at this time. In actuality they are under-run since they have completed 70% of the task and not just the 50% in the plan.

The SV and CV variances are sometimes provided in percentage form rather than in actual value.

Forecasting Using Earned Value

The variance calculations for SV and CV give us specific values of under-run/over-run. We can also calculate indices that give us trends and that can assist in the estimating of final project cost. The two indices generated in the Earned Value technique are the Schedule Performance Index (SPI) and the Cost Performance Index (CPI).

SPI = EV / PV

The SPI is the ratio of Earned Value over Planned Value. When the EV is greater than the PV, we are doing more work than scheduled and the project is accelerating. The SPI will be greater than 1 in that case. When EV is less than PV, we are doing less work than scheduled and the project is being delayed. The SPI will be less than 1.

CPI = EV / AC

The CPI is the ratio of Earned Value over Actual Cost. When the EV is greater than the AC, we are completing the work for less than the estimate and the project is under-running. In that case the CPI is greater than 1. When the EV is less than the AC, then the cost to complete the work was greater than the initial estimate, or value, of the work. In this case we are over-running and the CPI is less than 1.

A question frequently asked of project management is, "How much will this project really cost to complete it?" At the beginning of the project an estimate is made. This estimate is normally set as the project budget and is referred to as the Budget at Completion (BAC). This is also the final PV for the project when the project plan is created. But the BAC contains many assumptions and is seldom realized precisely. Therefore, the question is a legitimate one. As the project progresses and we learn more, the assumptions are proved true or discredited.

Project management is then called upon to make a new estimate of the final cost to accomplish the project. This estimate takes into consideration the current business conditions and the relevant project experience to date. It is referred to as the Estimate at Completion (EAC). The EAC is the answer to the original question. It includes all of the money spent so far on the project and an estimate of what must still be spent to complete the project work.

EAC = AC + ETC

The Earned Value technique uses the variances and indices to calculate an EAC. This is done by taking the results of what has been spent already on the project, the AC, and adding to that an estimate of the cost to do the remaining open work on the project. This estimate for the remaining work is referred to as the Estimate to Completion (ETC).

It is obvious that in order to have an accurate estimate for the final project cost, the EAC, we need to calculate the ETC. There are several methods. These four are the most widely accepted.

Method 1. In this case I consider that whatever cost variance that has occurred on completed tasks is an isolated event. I do not think it is a trend and therefore the original estimate for the cost to complete the remaining work is unchanged. In this case the ETC is the value of all the work on the project that has not been done yet. It is determined by taking the total value of the work on the project (BAC) less the work that has been completed (EV).

ETC1 = BAC - EV

Method 2. In this case we consider that whatever cost variance that has occurred is a good indicator of what we can expect in the future, so we will extrapolate the trend through to the end of the project. This is done by determining the remaining work on the project (see Method 1) and dividing that by the CPI; which indicates the trend of under-run or over-run.

ETC2 = (BAC - EV) / CPI

Method 3. In this case we assume that there is a need to complete the project on time. Therefore, if the project is behind schedule, an effort will be made to accelerate the remaining tasks. This acceleration will cost money so the remaining work is also divided by the SPI; which indicates the trend of schedule variance that must be overcome to complete on time. Normally when this method is used, the estimate for the remaining work is based upon the Method 2 approach of considering any over-run or under-run trend.

ETC3 = (BAC - EV) / (CPI * SPI)

Method 4. At times we become convinced that the original estimate is so far off, or that the variances are neither isolated or clear trends, that we create a new estimate for the remaining work. This is often done when schedule acceleration techniques such as crashing or fast-tracking are used.

ETC4 = New estimate for the remaining work

The project management team uses whichever method they believe is the most accurate way to estimate the cost of the remaining work. Ultimately this is a judgment call based upon their understanding of the project.